Use your power for good: An ethical scicomm framework for making a difference in the academy

Borrow these ideas today! (A conceptual framework, a reflection tool, and an action plan you can put to work immediately)

As regular readers well know, I leverage evidence-based scicomm approaches to create tools that people can use to take action to make their efforts to share science more effective and ethical. I’m driven to create these tools (and to conduct the underpinning research) because ethical science communication is vital, given that we hope society will use science to make policy, civic, and personal decisions.

Unfortunately, institutional and systemic hurdles in academia complicate, constrain, and undervalue efforts to share science effectively and ethically.1 After years of working within our own institutions to help them recalibrate, some collaborators and I2 recognize that:

Plenty of other people also think academia/higher ed can be better. In fact, there are thousands of specific or abstract ideas about this (many of which can be productively found in online repositories, peer-reviewed journals, conference proceedings, and public-facing commentaries).

Simultaneously, many of our colleagues do not recognize, understand, or perhaps even do not value the specific needs for change (toward more institutional support of ethical scicomm) that we prioritize.

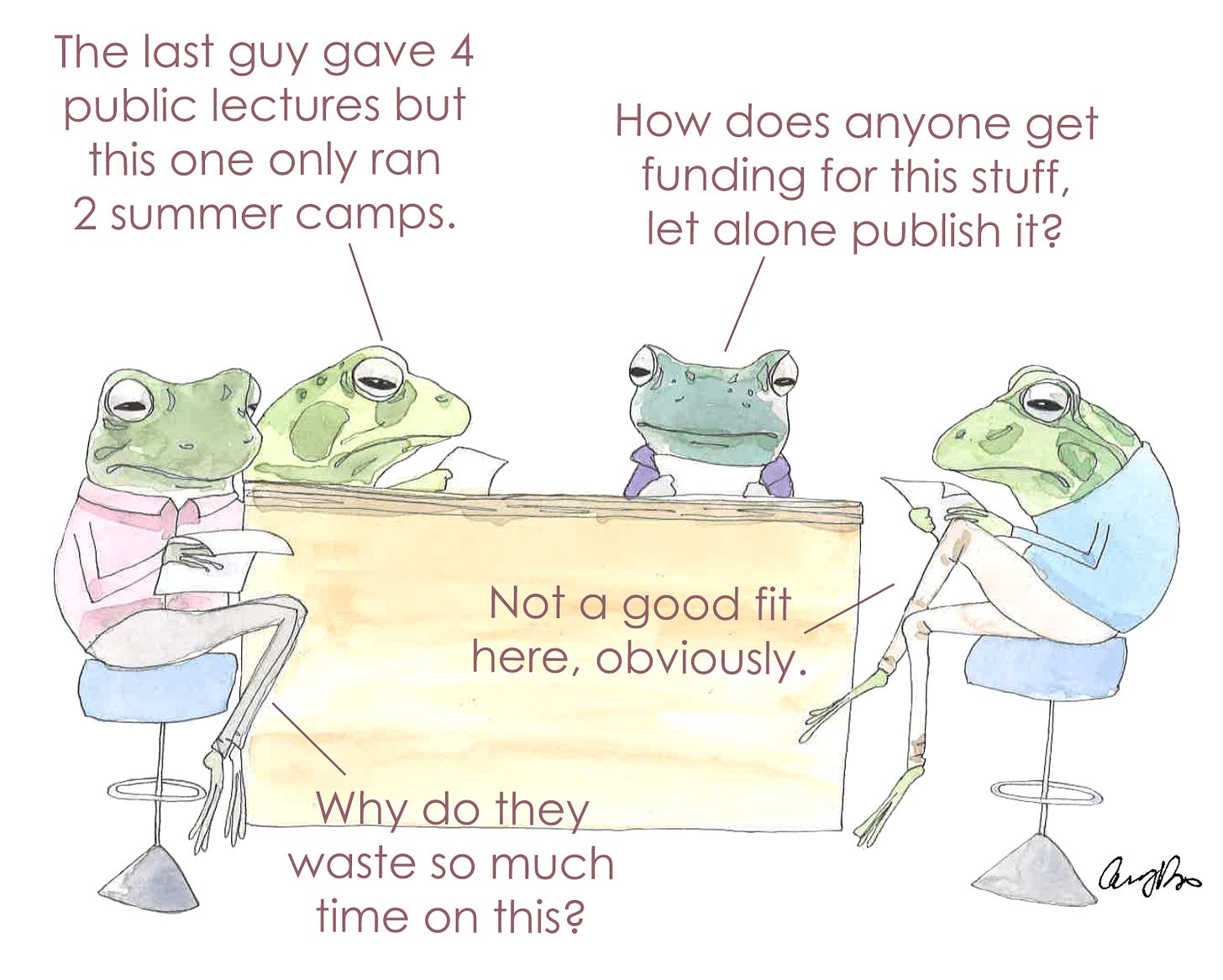

One of the major hurdles between points 1-2 is what my collaborators and I shorthand as the academic prestige paradigm, an underlying set of hierarchies and values that have shaped the academy since its inception. Notably, scicomm and the people who do it are not valued in the prestige paradigm.

To change this dynamic, we need to be able to recognize and understand what the prestige paradigm is and how it works. However, the prestige paradigm is so embedded in academia that it is mostly invisible.

For instance, in my department and related programs there are no required courses in ‘history of science’ or ‘philosophy of science’ or the like that would reliably articulate for the students we train (and thus our own faculty) the historical origins of this prestige paradigm. Without this context, it is virtually impossible for my colleagues or the students we support and train to recognize how the prestige paradigm plays out in their attitudes and behaviors about what is valuable, scientific work and what is not.

The result is that my work (and the work of faculty, staff, and students also working in scicomm) is frequently disregarded as “service,” that required but distained, deemphasized aspect of academia that actually provides most of our institutional and societal impacts. Put another way, because scicomm (and people doing it) aren’t (typically) valued as ‘true’ scholarly work, the classes I teach, the research I conduct, the many ways in which I support students and colleagues to do it well, and the efforts of other people doing it are all seen as less valuable, less necessary, less prestigious. There are downstream ramifications, including people not learning to ethically and effectively share science and people being passed over for jobs, promotions, and funding. And, as I’ve written before, if we don’t change this paradigm to embrace evidence-based, ethical ways of sharing science, we cannot possibly expect anyone (including upper administrators) to see value in the science we do. If people beyond our labs and departments don’t value our science, they may be suspicious of it, criticize funding allocated to it, and even actively seek to stop us from doing it.

These negative feedback loops are predictable.

And we need to stop fueling them with an academia-wide distain for the vital, robust, effective work done in scicomm courses, scicomm projects, and the many scicomm programs operating beyond academia. We also need to equip ourselves, our colleagues (at all career stages), our administrators, and the next generations of science-trained professionals to share science. This means flipping that anti-service/anti-scicomm paradigm on its head.

And I know. You’re tired. I’m tired.

We all need a nap, and a magic want that resets the world to the way we individually and collectively think it should be. But the reality is that we are the magic wand. We wave ourselves, as academics.3 I can’t help but think of this as an opportunity, albeit a challenging one!

Perhaps you, too, have been slogging away at this shift for years. Or, maybe you’re already game for that effort, but you’re not sure quite what comes next. Instead, it could be that making change in your degree program, department, or wider university setting feels impossible, and the scale of change needed basically immobilizes you. In any case (or wherever you fall in between) you’re in the right place.

Because, colleagues and I spent the past two-plus years articulating an overview of specifically how the prestige paradigm needs to change. We’ve also developed a framework for how you can reflect on what level of influence or change-making capacity you may have individually. And, we’ve drafted an extensive action plan of what you can do now, and then next. The entire framework was published in the peer-reviewed journal BioScience, and you can access it (and the supplements) here, on my website. You can also access the striking illustrations we commissioned to illustrate the current paradigm and what we can do individually and institutionally to foster scicomm instead. Those illustrations are available here as printable posters you can download and display!

Please contribute to our collective efforts to support each other and make the world a bit better. You can share, like, and comment on School of Good Trouble by subscribing, gifting a subscription, and referring a friend.

I have written about this at length, here on School of Good Trouble, and in numerous other outlets. Check my archives for plenty on how this manifests.

We’re not alone here, and we’re not pointing to anything novel. We are in good company among countless other scicomm professionals and scholars, along with everyone who’s ever tried to shift the academy towards the greater good in other disciplines, too.

I’m not discounting the very real logistics, bureaucracy, etc., that complicates our self-governance. But so far, we still have more autonomy than most sectors.